An American Trilogy part 2

squeezing the last few drops of nectar from decay

Will Blythe picks me up at the bus station in Jackson, Mississippi. We met a few years earlier when he was studying architecture. I was fascinated by the South at the time but didn’t know any real Southerners, let alone natives of the Mississippi Delta. He had a sort of kindly vagueness about him that I found charming. He dropped out of college, left town, roamed around squandering his college grant, got married, and ended up in Jackson, with a wife and a child and a dog. I couldn’t figure out what he did exactly, but that seemed to be the case with most people I knew, myself included.

The air in Jackson seems cut with poison, the atmosphere stripped of all but tension. Farish street, the main black drag, and the ruins of the Hotel Edwards are visited before we return to Will’s apartment, close to downtown. His wife, a portly and querulous young woman, prepares a meal. She remarks upon how the blacks give her the ‘evil eye’ in the social security office and goes on to suggest that black women don’t get married so that they can collect more welfare money. “They hate us,” she firmly states.

I would be happier traveling alone but I can’t drive, a shortcoming that greatly limits my enjoyment of life and makes me dependent on people whom I wouldn’t otherwise choose to spend much time with. Following years of musical and literary immersion in the Mississippi Delta my first visit to that fabled region should be a momentous occasion. Will, being a native son, has an entirely different attitude. It holds no mythical allure for him. He doesn’t listen to blues records, doesn’t read Faulkner. He doesn’t listen to music or read at all.

We ride out of the hills in the clear February light, past kudzu mounds and swamps, a harsh wind blowing the car around on the road, through Lexington, a court-house surrounded by closed stores, Tchula, a little crossroads town, and into the red-brick labyrinth that is Greenwood, with its once notorious Ramcat Alley.

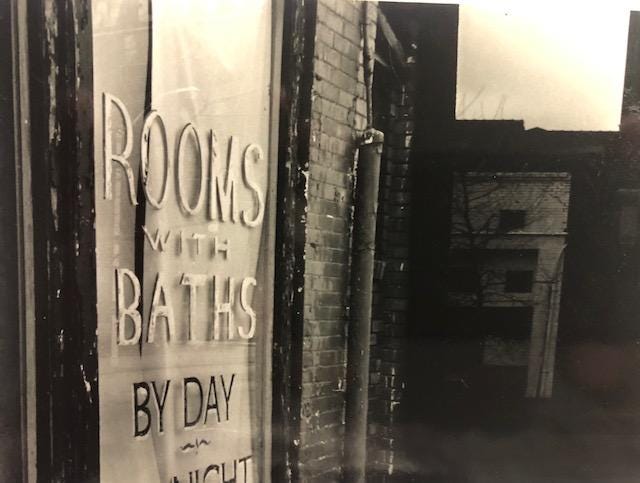

After so many years of dreaming about such places, my surroundings assume an unreality that, owing to lack of autonomy, I am unable to enter. I would like to have spent the night in the semi-residential hotel still operating in Greenwood, but Will figures we’re in some sort of hurry to meet up with his father in Clarksdale. The car isn’t running well and neither of us are well-funded. He’s more interested in drinking, swilling from a bottle of Kentucky Tavern as we drive up highway 49. We stop at a dilapidated roadside store called Elma’s Place, where we sit by the wood-burning stove and talk with Elma, who was born in 1905. She tells stories about alligators and tornadoes and Will employs that indulgent tone white Southerners often seem to use when they converse with their black brethren, which is perhaps supposed to suggest that they enjoy a closer rapport with their darkeys than the cold and condescending Northerner who looks down upon them could ever imagine.

Parked outside Parchman penitentiary, while inmates in their white prison garb till the fields, we split a blotter of acid.

A semi-hysterical woman in an antique shop in Drew, upon hearing my accent, guesses what brought me to the region and steers us in the direction of Wayne, a cross-eyed albino who runs a small record shop (mostly rap music these days) on the street that parallels the railroad tracks along which no trains run. Wayne directs us to Dockery’s plantation, where Charley Patton once resided.

I look down into the muddy Sunflower river and don’t feel particularly moved, unable to savor such a long anticipated moment. A car full of old ladies looks us over suspiciously as they drive up the lane to what, presumably, was Mr. Will Dockery’s house.

The owner of a junk store where I buy a tin of antique laxative holds forth on the race question: “Folks down in Jackson think they can turn a n---r into a genius, but there ain’t no way you can turn a stupid person into a smart person.”

As we drive up Highway 61 Will regales me with one of his many grisly stories. This one concerns an old Mississippi college chum who was involved in a terrible car wreck: “his brains were coming out of his nose.”

At the Crowe’s Nest café in Mound Bayou, five young black guys are sitting at the counter, listening to a tape of their musical combo. We order a couple of cans of beer from the proprietor, Eunice, a strikingly beautiful woman. “I smell ribs,” says Will, whose ingratiating manner is becoming embarrassing. A current of lysergic anxiety pulses through me. “You don’t look old enough to have children,” I hear Will saying as I find myself staring at a plate of gristly beef with slices of Wonderbread on the side. I tell myself to remember to take my scarlet scarf with me when we leave.

Eunice complains about the crooked local police force. Will presses the young black guys for information about neighborhood spots. One of them looks at us a little hatefully. The town, Eunice tells us, is 99% black. The white population consists of a preacher and his two sisters. While rippling uneasily I manage to get the barbecue down as best I can. When we get up to leave Eunice asks my name. “John, one of the forefathers... means strong... strong John,” she says.

On Issaquena street in Clarksdale we stop at a junk store run by an old black lady named Bernice. She sits by the heater with an old man. When I tell him where I live he keeps muttering the word over to himself in a wondering way: “California... California... California.”

As we walk out a ragged old-timer with a bundle of clothes under his arm calls out, “Hey white folks.” He had heard me asking Bernice about old records and claims he has exactly what we’re looking for. He waves a cassette tape at me. Apparently it contains selections from his record collection. We sit in his car and he slips the tape into a machine. O.V. Wright’s ‘A Nickel And A Nail’ blasts out. A younger guy sprawled out in the back seat wakes up. “What’s happening?” he says, and falls back to sleep.

Will buys the tape for five dollars and we enter his father’s clothing store, the oldest haberdashery in town. The ragged old-timer leans across the counter, exposing his chapped, cracked, peeling fingers, and asks Will’s father if he has any whiskey. A singularly slimy-looking Pentecostal preacher dressed in an overcoat with a yellow ribbon in the lapel, enters and petitions Floyd Blythe for a monetary contribution. Floyd says something about the preacher being “one of the good ones... a better class of black.” The young guy who had been sleeping in the back of the car walks in. “Are you from around here?” he asks me. “No, why d’you ask?’” – “Because you don’t look like you’re from around here.”

Cotton fields spread out on both sides of the road with bare trees on the distant horizon. I realize, much to my horror, that I have left my long-cherished scarlet scarf in Mound Bayou. We pass the old Stovall Plantation. Smoke and tension fill the car. Driftwood and beer cans are piled high along the banks of the river at Friar’s Point, where Will used to ‘party’ when he was a teenager. We walk away from each other. The wind is bitingly cold. When Will returns to the car he tells me that he has been weeping.

We drive across the bridge into Helena, Arkansas - once home to Sonny Boy Williamson and the King Biscuit Time Flour Hour - one of the most untarnished towns I have ever had the unearned pleasure of beholding. I would like to behold it for longer, but Will is intent on getting to Memphis.

We park outside an antique store. I’m getting out of the car—which is beginning to resemble a mobile dumpster with morbid growths infecting some articles buried knee-deep in the back seat—and holding my fountain pen, when the fountain pen is removed from my hand, as if snatched by an unseen force. Subsequent thorough inspection of person and vehicle yield no pen. What do I know about the Mississippi Delta? Nothing, just myth and history, and I’m presumptuously looking for a point where the two connect, and I can’t find it. I took from the Delta and the Delta took from me: my scarf and fountain pen, no less. I should have been melting into the acid glow but I interpret these strange losses as ill omens, and let them addle my mind.

The sun sinks, the car starts stuttering. We pull into a gas station/beer parlor combination in Lula, a ‘short old town’ seemingly lost in the woodsmoke past (an old haunt of Charley Patton’s - “when I was livin’ in Lula, I was livin’ at ease”). Through the window a crowd of black faces laugh at us. One old man and a snickering youth help with the car. All it needs is water, a necessity neglected by Will.

Will’s sister, Louise, lives with her husband in an affluent section of mid-town Memphis. Their house is bare, the television is on all the time. Over the previous year Louise has suffered two miscarriages. “I play a lot of patience,” she says.

She serves us spaghetti at a circular glass table held up on aluminum stilts. Her husband, Harry - the 25-year-old heir to a shoe-retailing fortune - sleeps on the sofa. Later, when he wakes up, we have a few drinks and sit around talking. He opens a conversation on ‘the race question’ with the now familiar qualification, “I’m not racist but...” And to prove it he throws some insufferable sunglasses-and-beards ballsy white boy blues on the turntable. I hadn’t realized that anyone actually listened to such stuff. But there’s a target group out there: aging frat boys like Harry.

Exhausted, I retire to the trinket-filled bedroom of the long-awaited child, and fall into a deep sleep.

On a cold Saturday morning I take advantage of the opportunity to spend a few hours alone. Some unfriendly comments are directed at me as I walk the length of Poplar avenue. “Have you got a cold?” I’m asked in a threatening tone as I pass some grim housing projects, apparently cutting a pitiful figure.

Ducks waddle in the fountain of the Peabody hotel and the player piano plays ‘San Antonio Rose.’ Will shows up and we have lunch at the Bon Ton cafe. “This place is emptier than a Jewish pay toilet,” he remarks as we enter.

South Main Street, a gentle old thoroughfare, isn’t preserved, just left alone - but for how long can it remain in that state, in these times? We have coffee in the Arcade restaurant, opposite the abandoned Arcade hotel, now inhabited by squatters, one of whom closes the front door in our faces. Through a door left open for the purpose of ventilation, we find our way into the abandoned train station and take a tour of the various levels. Everything in the offices has been rotting for five years: ceilings have fallen to the ground, the floors are bestrewn with ancient ledgers and pieces of obsolete equipment. Cold wind seeps through broken windows, through which red-brick buildings dot twisting narrow streets. Only a small part of the station is in use. The ticket agent sits in his booth; he doesn’t care about trespassers. The building is up for sale at an asking price of $1,200,000.

As we enter Oxford, Mississippi on a rainy Sunday afternoon, Will points out five small crosses by the side of the highway, placed there in memory of five Ole Miss girls killed in a freak accident involving the rear-end of a truck during a bike-a-thon. It takes a lot of bum steers but eventually we find Rowan Oak, William Faulkner’s house. It is fascinating to observe the desk he wrote at, and the tiny typewriter he used, and the bedroom wall covered with his handwriting - on which he was mapping out A Fable - and the barn where he used to drink bourbon before sitting down to write.

I sit on the porch in rainy Jackson, listening to the wind chimes and the children in the school playground across the street, with a growing affection for that city’s dreary old soul.

In an antique store an old man named Hoyt tells us about a night some years earlier when he stopped at a roadside café in Indiana. “I hear you kill a lot of blacks in Mississippi,” ventured a fellow diner, upon learning where Hoyt was from. “Naw,” said Hoyt, “we don’t do that too much anymore - you see there’s a fifty dollar fine or thirty days in jail penalty nowadays.”

Will’s aunt Anelle calls up, asking if he would be so kind as to bring over some cigarettes to the halfway house where she is recovering from a drug problem. “She has a beautiful spirit,” says Will. “Her problem is that she never got out of the South.”

We drive into South Jackson and locate the place in question. Anelle is an attractive woman. She wears cast-off pants and a tartan shirt with lace cuffs; the care she takes with her appearance in such a dead-end place is somehow touching. She brings us plastic beakers of instant coffee; she does seem to have a beautiful spirit.

The halfway house is occupied by five women. A huge woman in a diaphanous nightgown sits in front of the television, staring at the floor. We adjourn to the laundry room to smoke. An orderly who is mopping the floor tells us that he’s studying to become a minister. What turned him around, he says, was witnessing a lady friend of his dying an HIV-related death in the back of the cab he was driving. He spent time in jail for drugs, robbery, and murder. One time, after he had been converted, he was on his knees in the church and they dragged him away. But he loved it in jail, there was church six nights a week, and that church, he says, “was on fire with the spirit.” He was sorry to leave that jail.

Elvis’s ‘An American Trilogy’ plays on the jukebox, fittingly it seems, in a bar called Martin’s near the bus station. As Will says, “Jackson in the rain, an empty bar, ‘American Trilogy’ on the jukebox, in the middle of World War Three: It can’t get much better than that.”

At the risk of repeating myself, brilliant. Hate when it ends.

This’s a good one: red brick apocalypse, thee, me, and Ellis Dee in the kudzu, always welcome for a time, as long as you leave town…